Melissa DeShaw, Abbie Joseph, and Grace Page (Advisor: Danielle Findley-Van Nostrand)

Background Information

In the midst of a pandemic, how have our relationships changed? Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we suspected that the number of individuals in long-distance relationships may have increased as a result of quarantine and travel restrictions. We also thought this may have disproportionately affected college students who were used to being in geographically-close relationships when they were living on their school’s campus. This shift from being in a geographically-close relationship to being in a long-distance relationship could be a major source of stress that ultimately decreases couples’ satisfaction, and we were interested in considering how this relational dissatisfaction could potentially be reduced in such unprecedented times. After researching relational maintenance behaviors, we decided to examine how the education and implementation of relational maintenance behaviors in college students’ romantic relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic could potentially affect satisfaction in their relationships. Relational maintenance behaviors refer to the several behaviors used to maintain a healthy and successful relationship (Weigel & Ballard-Reisch, 2001). The most common way to measure this is by using the Relational Maintenance Strategy Measure (RMSM) which contains five groups of strategies: positivity, openness, assurances, social networks, and sharing tasks (Stafford & Canary, 1991). These behaviors have been proven to increase satisfaction levels when implemented into a relationship (Weigel & Ballard-Reisch, 2001). Satisfaction was measured using the Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) which describes several relationship dimensions such as love, problems, and expectations (Hendrick, 1988). Several studies have been conducted on how the use of relational maintenance behaviors correlates with satisfaction, but there are no studies that have used an experiment to test this like ours did. An experiment allows us to determine whether something like relational maintenance behaviors may have a causal impact on satisfaction, and whether they may be able to change through intervention.

Methods

The 36 participants were recruited through Roanoke College’s SONA system in the psychology department and received 2 SONA credits for participating in all parts of the study. Participants had to have been in a romantic relationship. Participants signed up for a Zoom session where they were asked to complete a pre-survey in order to measure satisfaction within their current relationships. After the completion of the pre-survey, participants were asked to return to the Zoom session. Those in the experimental group were read a list of examples from the RMSM and encouraged to try some in their current romantic relationships, and those in the control group were asked to watch a 5 minute video about helpful habits for better sleep. The purpose of a control group is to have a base-line to be able to compare the changes in the experimental group to. Within a week, all participants received an email with a link for a post-survey, and their satisfaction in their romantic relationship was once again assessed using the RAS.

Results and Discussion

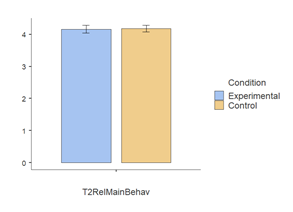

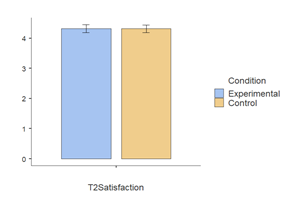

Contrary to expectations, participants in the experimental group, who received the informational session on relational maintenance behaviors, did not report more satisfaction at the time of the post-survey compared to the time of the pre-survey. Additionally, participants in the experimental group did not report more satisfaction than participants in the control group at the time of the post-survey. However, we did find that participants in both the control and experimental groups who reported using more relational maintenance behaviors at the post-survey also reported more satisfaction at the post-survey. Participants in both the control and experimental groups who reported more use of relational maintenance behaviors at the time of the pre-survey also reported more use of these maintenance behaviors at the time of the post-survey. Also, participants from both groups who reported high satisfaction at the pre-survey also reported high satisfaction at the post-survey.

Relational Maintenance Behaviors (Post-Survey)

Satisfaction (Post-Survey)

Due to our very low sample size, the inability to have face-to-face sessions, and the inability for us experimenters to monitor the relational maintenance behaviors of participants, we did not find what we had previously expected. We did, however, find what previous studies have found, as the participants reported more satisfaction when they used more relational maintenance behaviors in their romantic relationships.

Reflection

Through this process, we gained some much needed insight on what was beneficial to the success of this study, as well as what kept the study from reaching its full potential. First, we believe this study aimed to measure important variables and believe that a replication or partial replication of this study could result in significant and useful findings. Considering the majority of our findings were insignificant, however, we noted a few different aspects of our study that, if changed, may have led to greater significance. For example, the outcome of our study might have been significantly different if everything did not have to be done through online surveys and Zoom sessions. Additionally, we believe that the pressing SONA credit requirement for Psychology students at Roanoke College may have encouraged students to complete our survey for the sake of completion, rather than to provide quality data. If this study were replicated in the future, it would be important to ensure that the participants take the study seriously.

Conclusion

While we found that an information session regarding relational maintenance behaviors given to some participants did not significantly increase satisfaction, we found that all participants seem to already implement these maintenance behaviors in their relationships. The main finding from our study suggests that the use of relational maintenance behaviors in college students’ romantic relationships is associated with their relationship satisfaction, even during a global pandemic.

References

Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50(1), 93–98.

Stafford, L., & Canary, D. J. (1991). Maintenance strategies and romantic relationship type, gender and relational characteristics. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8(2), 217–242.

Weigel, D.J., & Ballard-Reisch, D.S. (2001). The impact of relational maintenance behaviors on marital satisfaction: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Family Communication, 1(4), 265-279.